One vet describes how his unit pre-scheduled a second truce on New Year's Day because the Germans wanted to see how the pictures turned out. Because they traded caps and jackets, it's impossible to distinguish the opposing armies in [this] photo...

I've heard of this story, and seen the program (in the video) before. However, it particularly feels resonant for this time period. I sense that more and more soldiers are seeing (and will see) the Light, and in that Light, recognize that all wars are bankers wars, and that they are simply fighting and dying to feed the war machine.

"Mainstream history textbooks go on at length about the 1917 Russian revolution that ended Russian participation in World War I. They rarely mention that the revolution spread to Germany the following year. A combination of revolutionary fervor and severe food and fuel shortages would lead to a series of three mutinies by German sailors."

--------------------------------------------------------------------

Suppose They Gave a War and No One Came

The 1914 Christmas Truce

2014 year marks the 100th anniversary of the Christmas truce during World War I. On December 25, 1914, two-thirds of the Western Front (roughly 100,000 British and German troops) spontaneously exited their trenches to exchange chocolate, cigarettes, brandy rum and souvenirs. They took photos of themselves together, played football (soccer) and shared gripes about the war and their superior officers. In some areas, the truce continued for days.

.

http://youtu.be/8WgPi_me1p4

Short truces between British and German units dated from early November 1914, when static trench warfare began. The close proximity of trench lines made it easy for opposing armies to shout greetings to each other. It seems to have been the most common method for arranging informal truces during to attend to the wounded and collect the dead for burials. Several British soldiers recalled instances of Germans asking about the outcome of important football matches.

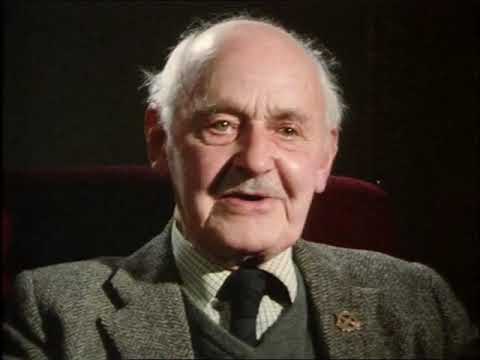

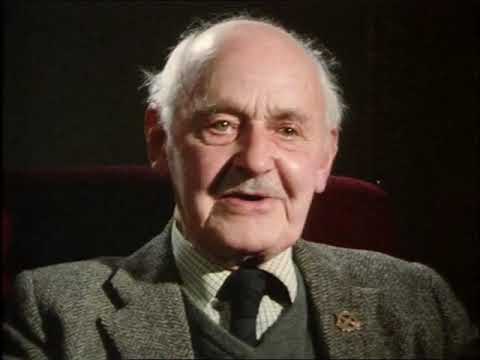

This 1981 BBC documentary features interviews with two British veterans of the Christmas truce. One vet describes how his unit pre-scheduled a second truce on New Year's Day because the Germans wanted to see how the pictures turned out. Because they traded caps and jackets, it's impossible to distinguish the opposing armies in the photo below:

High Command Livid

Soldiers naturally wrote home to their families about the impromptu truce. The British high command was livid when the New York Times broke the story on December 31, 1914.

Over the next three Christmases they issued strict orders that any troops who fraternized with German soldiers would be court martialed for treason. Despite the dire warnings, a few British troops participated in spontaneous celebrations with German soldiers in December 1915.

The German Revolution that Ended World War I

Thanks to the Christmas truce, soldiers on both sides made the shocking realization they had more in common with each other than with their superior officers – despite the intense propaganda they were fed by their respective governments. In 1918, a longer better organized mutiny would force the German Kaiser to surrender to the Allies.

Mainstream history textbooks go on at length about the 1917 Russian revolution that ended Russian participation in World War I. They rarely mention that the revolution spread to Germany the following year. A combination of revolutionary fervor and severe food and fuel shortages would lead to a series of three mutinies by German sailors.

During the third mutiny, on Oct 29, sailors stationed in the port city Kiel organized armed demonstrations that spread throughout the fleet and docks. By November 3, the entire city was controlled by a revolutionary council. Success at Kiel led to huge demonstrations across Germany. Within days, scores of German towns were controlled by councils of workers, soldiers, and sailors.

As Neil Faulkner writes in 1918 How the War Ended, the revolution reached Berlin by November 9:

Hundreds of thousands were on the streets. The city was awash with red flags and socialist banners. The anti-war revolutionary socialist Karl Liebknecht addressed the crowds from the balcony of the imperial palace and proclaimed a 'socialist republic' and 'world revolution.'

Once the popular uprising reached the German capitol, Kaiser Wilhelm would have no choice but to surrender to Allied forces on November 11.

Photos from Wikimedia Commons

No comments:

Post a Comment